This article is based largely on a talk titled "My Two Years Amongst the Huns" given by George Mulford to an audience (unknown) on 12th October 1919. The complete manuscript is held at the Imperial War Museum Department of Documents (84/41/1). Every effort has been made to obtain permission from the copyright holders.

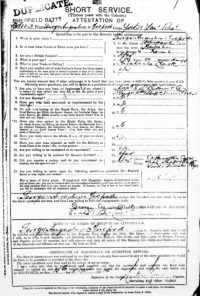

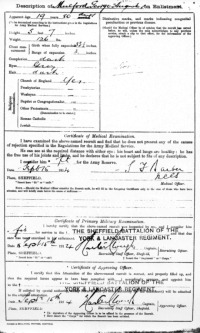

Above and below left: Pages from the Service Record of George Augustus Mulford (Public Record Office WO364/2622). Note on pages 3 and 4 that George was originally reported killed in action on 1st July 1916.

George took part in the fateful attack at Serre on 1st July 1916 when he sustained grenade wounds to the thighs in reaching the German front line and was taken prisoner. "On that ill fated day for our city I found myself in the early hours of the morning taking cover in a special assembly trench about a mile from the German front lines. Everyone was buoyant and confident in our success and at 7.30 AM the 4th wave to which I belonged went 'over the top' towards No Man's Land. What transpired between that time and 7.45 AM can hardly be described as it will always remain to me a nightmare of bewildering accidents and confused succession of disasters. Having been wounded and seen nearly everyone killed or wounded around me I made little resistance against the 20 or so Germans who found a comrade bandaging my wounds in a dug-out, and I was in a strange measure relieved to think that something tangible had happened, the import of which I was too dazed to understand." Seeing that his captors appeared to be a "very peaceable crowd" George decided to try to cultivate comradeship. "....I tackled the most jovial looking of them. He seemed delighted to reply in Excellent English and introduced himself by saying that he had been a waiter in a London restaurant, adding that he was sure that he had met me before under happier circumstances. I could not refrain for leaving his happy delusion undeceived and at once recognised an old friend "Why its old Max" I said. "Why of course - don't you remember how you always asked for a mutton chop on Mondays" he replied, and thereupon all vestige of reserve went by the board and we were great friends. He explained to his comrades this fortuitous 'rencontre' and I was soon made to feel at home. Several proffered spare bandages and Max busied himself binding up a wound I had hitherto unnoticed. Others shared chocolate, tinned stuff and one insisted on my having a somewhat battered cigar, so that I felt quite at ease." It hadn't yet sunk in that he was a prisoner of war - no-one had searched him and in Max he had found a guardian and protector. His captors were mostly students and impressed him by their stature and and quiet earnest manner. George remained in the dug-out overnight before being carried back to a Dressing Station in the rear trenches. There a medical officer re-dressed his wounds and offered him cognac. The two men fell into conversation using French as a common language. "On my stating that numbers of our fellows were lying out in No Man's Land he volunteered to go out with a search party and did so that night. The following morning he seemed quite annoyed and on my venturing to enquire the cause, said that he had always respected the English for their clean manner of fighting and that he was surprised to find that this was no longer so seeing that he and his stretcher bearers had been attacked from the rear by our patrols and had only escaped by precipitate flight. I assured him of the misunderstanding on the part of our fellows as to his intentions, and succeeded in mollifying his indignation." The medical officer later arranged for George to be carried a distance of 4 miles (6km) down to a motor-ambulance. The kindness and consideration that had been afforded by the enemy up to this point had clearly surprised George. Remarkably, the further he travelled away from the front line, the harsher and less sympathetic his treatment became. The next stop for George was St. Quentin, where he was housed for three weeks with around 200 other wounded men in the Municipal Hall. He had no complaints of his treatment here, and it seems that the staff treated the prisoners of war and the German wounded equally. George described the German doctors as working like Trojans day and night, and the nurses as being on duty for 14 to 16 hours each day seeing to every need without complaint. The doctor in charge even turned a blind-eye when French civilians smuggled in delicacies for the Allied wounded. From St Quentin, George and other wounded prisoners of war were ferried by hospital train into Germany, passing through Namur, Liège and Aachen. Their reception at the German border town of Aachen was distinctly chilly. George recollected the nurses who boarded the train here turning hostile on learning that their patients were not German but English. The train journey continued through Köln to its final destination of Ohrdruf on the edge of the Thüringer Wald in central Germany.

The hospital at Ohrdruf consisted of seven huge wooden Lazarettos for the seriously wounded cases and canvas-topped ramshackle barns for the rest. The barns provided little protection against the weather, and the occupants became accustomed to a soaking whenever a rainstorm passed. At first there were no more than two doctors and two orderlies to care for almost 1,000 wounded. Until the arrival of 30 orderlies - English, French and Russian - from a neighbouring camp, George and his fellow prisoners received little attention, and were fortunate if they had their wounds dressed as infrequently as once a week. The situation improved a little more with the arrival of several French and Russian doctors, but each had 70 or 80 seriously wounded patients to care for under appalling conditions. George put his language skills to good use by interpreting for the medical staff. Until more substantial food was delivered from a neighbouring camp some five weeks after George had arrived, there was little to eat. In the morning, there was brown rye bread and black 'coffee' made out of rye which tasted like charred toast. Midway through the day a bowl half-filled with a watery potato soup, a little mutton, and 'coffee' was typical fare. In the early evening there was more of the unappetizing soup. Despite these privations, the temperate climate, clear air and beautiful landscape combined to make life bearable. By December 1916, the hospital at Ohrdruf was nearly cleared and George - his services to the medical staff no longer required - was transferred to the neighbouring prisoner of war camp of Langensalza, a place that George described as the most sinister camp in Germany. "Think of the conditions of 12,000 men huddled together on a large sized ploughed field so situated that it caught all the water draining from the surrounding hills. Sanitary arrangements on a par with those of the native quarter in an Egyptian town. Food of the vilest and unhealthiest nature for human consumption. Long ramshackle dilapidated barracks to hold 7-800 men with no thought in their construction for comfort and accommodation." George described the guards at Langensalza as being the most brutal and ferocious that he ever saw. Before leaving Ohrdruf, George had kitted himself out for comfort and warmth in scarlet trousers, blue tunic, an old kepi and "an ancient comically cut overcoat which must have been worn by its [French] owner in the 1870 war of which he yarned so much." Thus attired he readily passed for a Frenchman and by making friends amongst some of the French N.C.O.s who held priviliged posts in the camp, he was able to escape some of the harsher treatment from the guards. George was also now receiving regular supplies of food parcels from home. George's stay at Langensalza was short, for early in 1917 he was transferred to a camp at Kassel, where conditions were less harsh. George had so far avoided being put to work to aid the German war effort, and was quick to see that he could keep to his policy by putting himself forward for clerical duties. "The timber cutting season was in full swing on our arrival and soon nearly all my companions were out on Kommando, as the Germans called the allottment of prisoners of war to work outside the camp. I saw that something might be done by having an Englishman in the camp office who might be able to have a say in matters, so I commenced clerical [work] looking after the 200 and odd of our fellows. George spoke of the horrors he witnessed in an adjoining camp which held Belgian civilians who had been deported after refusing to work in German factories or in munitions factories in Belgium. "[The Belgians'] rations were a half bowl of watery soup every 3 days and 2 oz of black bread daily. Hideous skeletons they fought and tore each other to pieces for a crust of bread. At night they would scale the wall which divided them from our camp at the risk of being bayoneted and would implore one on their knees to give them anything refuse we had." In the spring of 1917, George witnessed the arrival of thousands of Russians who had been working in the German lines in France. "To see them coming in made one mad, stark mad with a passion that such atrocities could be perpetrated. They dropped and died on the road in sight of camp - they had no semblance to human beings with a vacant awful expression in their eyes, cheeks shrivelled and eaten away and their jaw bones standing out with a skeleton like grin." The prisoners of war at Kassel did at least enjoy some possibilities for recreation. "The camp authorities were quite decent in some respects and allowed us to have a football field, a theatre, a library and facilities for study. Our 'Polyglot Society' was quite a good one and I had plenty of opportunity of discussing and debating with French, Belgian and Russian students of which there would be about 200 in the camp. Boxing of course was a very popular pastime and great international contests took place generally to the credit of our fellows. Everyone tried to play some kind of instrument and each barrack possessed what one would now call a 'Jazz Band'. In August 1917, George was moved again, this time to a punishment camp in northern Germany, having had a serious altercation with a German N.C.O. The camp held about 500 men, all from the British Empire, and discipline was rigidly maintained. For once, George was unable to avoid Kommando. "....25 of us were picked out one day for Kommando. Although I protested and argued it was unavailing, so I made the best of things and decided I would be as stupid and obstinate at work as possible. We trained to a tiny village about 20 miles from Soltau and learnt that we were to become farm hands as the harvest was in swing." George thoroughly detested the farmer whom he regarded as a blatant profiteer "who worked his farm by the sweat of the dozen or so prisoners he tyrannised and swindled his own Govt whenever he could." In the end, the farmer found his British farm hands to be more trouble than they were worth and had them removed to a sugar beet factory. "....we hardened our hearts on arrival and narrowly missed being clubbed to death by the guardians of the place who made life one long drawn out misery. George was to remain at Hameln for 8½ months until he was exchanged to Holland in July 1918. Hameln was a large camp with a population which fluctuated between 15,000 and 20,000 as working parties came and went. George commented that "nearly every European and several Asiatic nations rubbed shoulders and made up a bedlam of tongues and customs. The sight on the main street (Hindenburgstrasse) on a Sunday afternoon when everyone had put on their best clothes was one which gave food to the imaginations." George soon found himself work as an interpreter and general factotum in the large camp orderly room. He was one of 60 or so of all nationalities in the office. His days at Hameln were filled with "insignificant little happenings and tastes - clerical work at the office, writing out the translations of some half dozen German daily papers, work on the Red Cross Committee, sport, amateur theatricals and debating societies, schoolboy midnight feeds with friends, and teaching, not to mention sundry encounters with officious Huns, which once resulted in a change of food and more solitude in the Arrest-Haus." In the early spring of 1918, George thought seriously of making an escape attempt. "About the time that I had got everything in readiness and was making plans to get out of camp in a wagon covered over with sacks of parcels, I saw an excellent opportunity of getting even with the Huns and having a little excitement in the bargain. The Exchange of all N.C.O.s who had passed over 18 mos in captivity was in progress and I had charge of the registers of those eligible for this Austausch. George safely crossed into Holland, and was eventually repatriated to England on 22nd November 1918. © Andrew C Jackson 2003

|