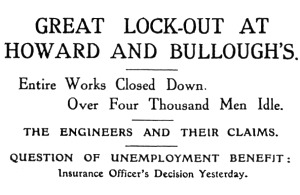

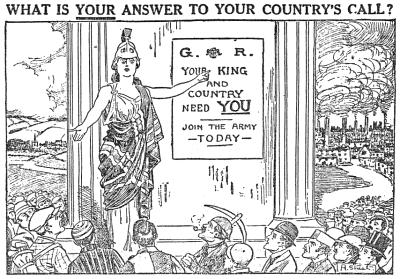

In August 1914, the prospect of war against Germany was of less immediate concern to the people of Accrington than the continuing lock-out at Howard & Bullough's machine works, the town's major employer. Accrington's prosperity had been built on the spinning and weaving of cotton, but by 1914 the industry was already in decline. Following the refusal of Howard & Bullough's management to meet the demands of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers (A.S.E.) for trade union recognition and a minimum wage1, up to 600 engineers at the works went on strike on 2nd July. Six days later, the management locked-out the whole workforce of nearly 5,000 men and boys. Although members of the A.S.E. received £1/week lock-out pay while on strike and 1,100 members of the Gasworkers and General Labourers Union received 10s (50p)/week, some 2,000 non-union workers were left without any income.2 As the lock-out at Howard & Bullough's continued throughout August, the small British Expeditionary Force was engaged in bitter defensive battles at Mons on the 23rd and at le Cateau on the 26th. An emotive article published in the Accrington Observer & Times of 29th August under the byline of T. Clayton used news of the fighting to bring pressure on the striking engineers to return to work:- Men of Bullough's, what are you doing in this time of stress and trial? Shall I tell you the plain and unvarnished truth? You are daily wasting bright golden hours in registering yourselves at your club house. You are sitting on your heels on the kerbstones twiddling your thumbs. You are propping up the railings of the Ambulance Hall. You are trapesing aimlessly through the the already too crowded streets. You are lounging, sitting and standing near the war office in Dutton-street discussing tactics and methods of a warfare in which you will not, either with hammer or gun, play your part for the honour of your country.3 An impassioned appeal by Lady Louise Selina Maxwell for Englishmen to take up arms for their country appeared in the same edition of the newspaper.4 Although her words make bizarre reading to later generations, the tone was not uncharacteristic of the time.

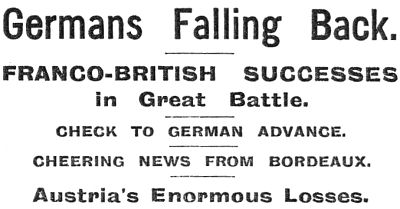

It was during the last days of August that the first Pals battalions were raised in Manchester and Liverpool. Largely through the initiative of Lord Derby, cities and towns were being allowed to raise at their own expense battalions of local men who would serve together for the duration of the war. A letter to the editor of the Observer & Times from 'A Patriot' urged Accrington to follow suit:- We hear of great numbers of men coming forward in different parts of the country, and Manchester is earning itself distinction for the readiness of its men to offer themselves. Why not Accrington?5 Accrington's mayor, Captain John Harwood, would certainly have read the letter from 'A Patriot' with some interest. Harwood's mind was probably already working on similar lines and, on 31st August, two days after the letter was published, he contacted the War Office with an offer to raise a half-battalion from the Accrington district. Undaunted by the Army Council's reply that its policy was to accept no less than a full battalion, Harwood raised his offer on Sunday 6th September to one of a full battalion of 1,100 men. From across the English Channel, news of the fighting remained bleak. The British Expeditionary Force had fallen back across the Aisne by 30th August and four days later crossed the Marne, destroying the bridges behind them. On 3rd September, German cavalry patrols pushed forward to within 8 miles of Paris.

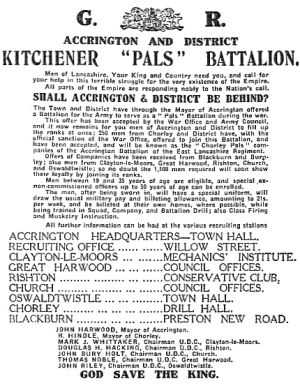

By the time the Observer & Times of Tuesday 8th September hit the streets, there was more cheering news all round. A Franco-British counter-offensive on the Marne launched three days earlier had relieved the pressure on Paris while, closer to home, there was confirmation that the War Office had accepted Harwood's offer to raise a full battalion. The task of raising 1,100 men from the Accrington district was a daunting one, particularly as several hundred young men from the town had already volunteered to enlist into other units.6 Harwood was probably greatly relieved when on the 8th he received an offer from Captain James Clymo Milton to provide 250 men from Chorley. In other respects, the timing was highly favourable for there was arguably more motivation to enlist at this time than at any other in the nation's history: an innate sense of duty towards King and Country was heightened by pressure from posters and newspaper comment as well as by lurid stories of alleged German atrocities in Belgium7; there was the prospect for many of escaping financial hardship, and there was the chance to serve alongside friends in a war which, with news of the German Army in retreat8, might well be over by Christmas. The Observer & Times of Saturday 12th September carried the first recruiting advertisement for the Pals battalion. Men of between 19 and 35 years of age were called upon to enlist, as were ex-non-commissioned officers of up to 50 years of age.9 Recruiting stations were to be opened in Accrington, Church, Oswaldtwistle, Clayton-le-Moors, Rishton, Great Harwood, Chorley, Burnley and Blackburn.

Recruitment began in Accrington and district at 2pm on Monday 14th September. A large crowd of applicants was reported at Willow Street School, which was the Accrington recruiting station.10 A total of 104 men were accepted in the first three hours, a creditable number given that many others were turned away for being below the minimum height and chest measurements of 5ft 6in (1.68m) and 35½in (90cm) respectively.11 Captain Harwood again telegraphed the War Office, and was given permission to reduce the minimum standards to 5ft 3in (1.60m) and 34in (86cm) in order to speed up recruitment.10

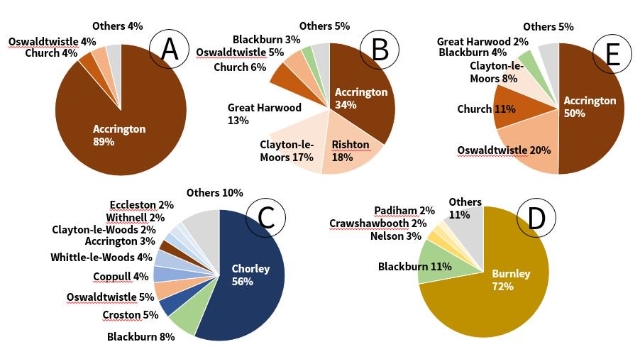

In the meantime, the battalion's officers were being recruited from prominent local men and their families. On the evening of Thursday the 17th, the following were recommended for commissions, to join Col. Richard Sharples (Commanding Officer), Capt. George Slinger (Adjutant), Capt. Philip Broadley (Company Commander), Capt. James Milton (Chorley Company Commander), Capt. Raymond Ross (Burnley Company Commander) and Dr. Gordon Watson (Surgeon): Harry Bury, Walter Cheney, Sydney Haywood, Thomas Harwood (grandson of the Mayor), Frederick Heys, John Kershaw, Harry Livesey, Anton Peltzer, James Ramsbottom, Thomas Rawcliffe, Walter Roberts and Arnold Tough.12 By the end of Friday the 18th, recruitment was almost half-completed with 508 men having enlisted, 250 of whom were from Accrington alone.12 The next two days of recruitment saw a further 276 men enlist13 and by Thursday the 24th the target of a full battalion of 1,100 men had almost been reached.14  Above: Home towns and villages by company (including the reserve company, E, recruited over the winter of 1914-15). In France, the Allied offensive had driven the enemy back across the Marne on the 9th, and across the Aisne on the 13th, but had now stalled. Trench warfare had begun and was to last for the next 3½ years.

© Andrew C Jackson 2021. In compiling this page, every effort has been made to obtain permission from the relevant copyright holders. Thanks are due to my wife Alyson for her great help in working through microfilm copies of the Accrington Observer & Times and Accrington Gazette, and to Maggy Simms for generously providing background material.

|